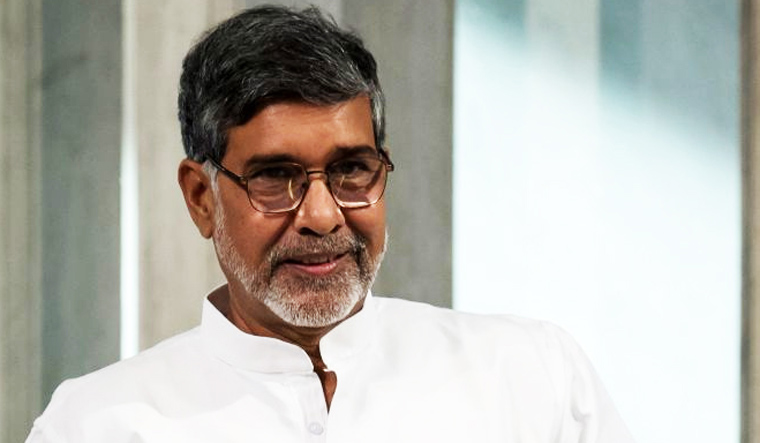

On the 8th anniversary of Kailash Satyarthi’s Nobel Peace win, Ajay Uprety, State Information Commissioner, Uttar Pradesh, shares his memories

My memories with Nobel Peace laureate Kailash Satyarthi date back around two decades. A benevolent and selfless personality, Satyarthi is someone who has stood tall even in the face of adversity.

It’s been eight years since the Nobel Peace Prize Committee conferred the coveted award on him. At this point, I am reminded of an incident that came as an eye-opener for me—one that highlighted Satyarthi’s determination to withstand all challenges.

It was in June 2004, when I was working as a journalist, that I received information from Satyarthi’s team about the engagement of minor girls at the Great Roman Circus in Colonelganj in Gonda district of Uttar Pradesh. I also learnt from his team that the girls were being mentally and physically exploited by the circus owner and his people. Satyarthi’s team was planning a major raid and rescue operation to free the girls from the circus.

As a journalist, I saw this as a perfect opportunity to be part of an exciting adventure and get first-hand experience of how these operations are conducted.

Day of the operation

On June 15, 2004, we started from Lucknow early morning with a large cavalcade of vehicles carrying activists of Satyarthi’s team and reporters from various media houses. Rakesh Senger, a senior member and longtime associate of Satyarthi, was leading the operation. We reached the circus spot at about 10.30am. We had no clue what awaited us—a nightmare was lurking around. I learnt that the police and local administration were informed about the operation, but on reaching there, I did not notice their presence.

Seeing a large number of people, the circus staff let us enter their premises and Satyarthi walked very deep into the middle of the premises looking for the poor girls. When the circus staff sensed that the operation is meant for rescuing the minor girls, they confronted us with iron rods and other weapons. They got violent and very aggressive towards us. Out of the blue, came a fully loaded pistol aimed straight at Satyarthi’s forehead. The man aiming the pistol was possibly the owner or one of his close relatives, who was threatening to take aggressive action against us if we did not get out of their premises immediately.

Amid this drama, the circus staff opened the cages and unleashed the animals including large bears, elephants and tigers onto us to strike fear and create chaos. They succeeded to a large extent, but Satyarthi stood his ground. Unfortunately, in a violent act, the man hit Satyarthi on his forehead with the pistol butt. Satyarthi started to bleed profusely and was writhing in pain. That did not deter him—even with his eyelashes drenched in blood, he kept searching for the children.

The whole scene appeared to me as one straight out of a Bollywood potboiler, but all this was happening in real life. In my whole career as a journalist, this was the first instance where I witnessed direct assault with weapons. Add to it, the trauma of wild animals being unleashed upon us. Suddenly I saw a foreign lady writhing in pain, dragging herself onto the ground and trying to escape the scene. She was instantly picked up by our colleagues and pushed into the standby vehicles to ferry our teams quickly out of the spot.

On our way to Lucknow, I updated many media houses about the heinous attack on Satyarthi and his team and told them about the harrowing experiences of the media team as well. We reached Lucknow by 4.30pm and Satyarthi was treated at a hospital. We failed to rescue the girls in the course of our operation, but as news spread about the attack on us, the administration initiated action and the culprits were brought to justice.

On our way to Lucknow, I updated many media houses about the heinous attack on Satyarthi and his team and told them about the harrowing experiences of the media team as well. We reached Lucknow by 4.30pm and Satyarthi was treated at a hospital. We failed to rescue the girls in the course of our operation, but as news spread about the attack on us, the administration initiated action and the culprits were brought to justice.

In all this chaos, I noticed Satyarthi’s immense inner strength. Even after receiving the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize, he is still as humble as ever. We still are friends and share a great personal rapport.

Originally published at The Week, 10 October 2022, available here.