This episode marked the start of 41 years and counting that Mr Satyarthi, now 68, has devoted to ending child labour and trafficking by fighting for children’s rights globally.

For “focusing attention on the grave exploitation of children for financial gain”, he was awarded the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, which he shared with Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai, who had fought for girls to receive an education.

Last Tuesday, Mr Satyarthi gave the keynote address at the Nobel Prize Dialogue 2022: The Future We Want Together held at the Raffles City Convention Centre, where Nobel Prize laureates, thought leaders and youth discussed wide-ranging global issues. The dialogue was organised by the Nobel Prize Outreach and Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore (NUS), in partnership with the Asian Medical Students’ Association Singapore.

Since Mr Satyarthi started children’s rights movement Bachpan Bachao Andolan in 1980, it has rescued about 120,000 children from exploitation. Acting on tip-offs, his organisation would go to mines, factories and quarries – often with the police in tow – to save child labourers as young as five or six years old. It also runs rehabilitation centres, giving these children an education, among other initiatives, to give them a better life.

His efforts led to the enactment of a law to prohibit child labour in India, among the many developments to end the scourge of child trafficking.

Mr Satyarthi also led a global movement called the Global March Against Child Labour, which resulted in the adoption of an International Labour Organisation (ILO) convention that all children have legal protection against the worst forms of child labour, such as slavery and sexual exploitation. The convention had been ratified by all 187 ILO member states by 2020.

He is also the founding president of the Global Campaign for Education, a civil society movement that promotes education as a basic human right. He also started GoodWeave International, a non-profit group that works to stop the use of child labour in global supply chains.

Mr Satyarthi’s zeal for the cause began at an early age, shaped by incidents he had witnessed. When he was five, he saw the son of a cobbler outside his school working alongside his father, instead of going to school.

“I felt very bad and disappointed as he had to work when we were all going to school. But my parents and teachers said it is very common for poor children to work to help their families.” he said.

When he was 11, his best friend dropped out of school due to poverty. Saddened by this, the young Satyarthi decided to start a charity drive to collect textbooks for poor children.

“I learnt the joy of giving at an early age,” said the father of two grown-up children.

He studied engineering in university as his late father, a policeman, had wanted him to have a lucrative career. But he worked as a lecturer for less than two years after graduation before the call of his heart to help others took over. In the course of his work, Mr Satyarthi has been beaten and received numerous death threats. Two colleagues were killed in retaliation for their work.

“What would happen to my wife and children if they had killed me? But that fear lasted a moment and the threats made me more determined to continue,” he said.

In 2020, it was estimated there were 160 million child labourers worldwide, down from 250 million in 2000. A report by the ILO and Unicef last year warned that nine million more children globally are at risk of being pushed into child labour by the end of this year as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Mr Satyarthi said Singaporeans can do their part to tackle the scourge of child trafficking by choosing products and brands that do not involve child labour.

So what keeps him going? “I once freed an eight-year-old girl from a stone quarry in India. She saw the rape of her mother and her brother’s death,” he said.

“She was very angry and very sad, and she asked me, why didn’t I come earlier?”

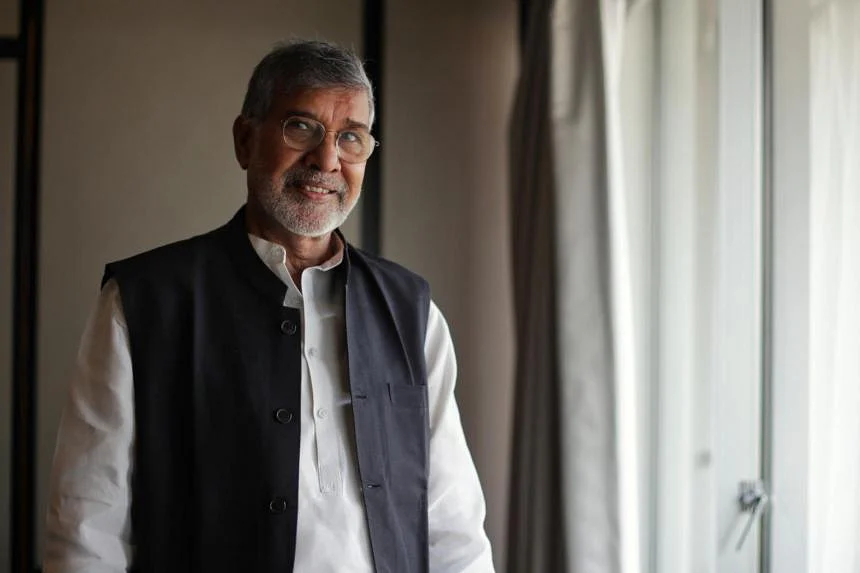

His life’s calling – saving children from exploitation

Mr Kailash Satyarthi was born in 1954 in India to a policeman and an illiterate housewife as the youngest of five children.

Though he studied engineering in university, he was an engineering lecturer for less than two years before giving it up to start non-profit group Bachpan Bachao Andolan, which means Save Childhood Movement. Aiming to end child trafficking and labour, the group has rescued about 120,000 children from exploitation since it was founded in 1980.

In 2014, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded jointly to Mr Satyarthi and Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai “for their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education”.

Mr Satyarthi has also been honoured with numerous awards, including the Trafficking in Persons Report Hero Award by the United States State Department and the Medal of the Italian Senate.

He is married with two children.

Young people from across Asia-Pacific, together with Nobel Prize laureates and international experts, took part in a series of conversations exploring the best path to a world with improved well-being for all.

Originally published at The Straits Times, in partnership with the Nobel Prize Dialogue 2022 and NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, 20 September 2022, available here. Image: Gin Tay, Straits Times