By Fawzia Moodley.

– Children’s voices took centre stage at the 5th Global Conference on the Elimination of Child Labour, which kicked off in Durban, South Africa, on May 15, 2022. Their voices resonated with the saying: “Nothing about us without us.”

The conference takes place at a time when child labour has increased worldwide since 2016 and amid a looming deadline to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development goal of eliminating child labour by 2025.

An estimated 160 million kids are held in labour bondage, with the prediction of a further nine million more joining their ranks due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the economic crisis in many parts of the world.

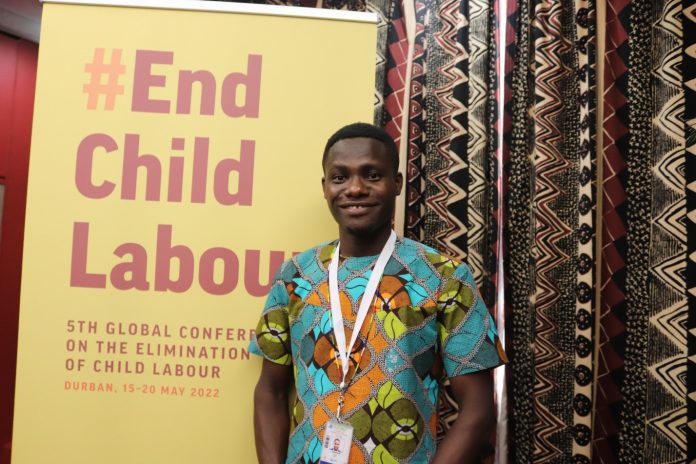

Lucky Agbavor (pictured above), a former child labourer from Ghana, caused a stir with his testimony of being roped into child labour at the tender age of four when his poverty-stricken mother sent him to live with a relative in a fishing village. While his mother thought he was being educated and cared for, the little boy was forced to work on a boat and almost died. Later he was sent to another relative.

“He took me to carry beams, load it in the forest,” the youth recalled. He managed to go to school, but working and studying were tough. He returned home after failing his basic education certificate in 2012.

“I came back home, and things were very rough,” he said.

But Lucky managed to get through high school by earning money selling ice cream, and today he is proof that anything is possible.

“In between, I put in all the efforts,” he said. Thanks to a Pentecostal Church scholarship, Lucky was able to study BSc in nursing.

“I hope to become one of the renowned nurses in Ghana,” he told the awestruck audience.

Thatho Mhlongo, a Nelson Mandela Parliament ambassador, was unequivocal.

“Child labour is not a rumour; it’s real as it’s happening worldwide. I have personal experience. I have witnessed a very close friend of mine having to work and fend for his family.”

She praised the conference organisers for inviting children and hearing their voices.

Thatho also acknowledged the South African government’s efforts to support children who were affected by the recent floods in KwaZulu Natal, which claimed hundreds of lives and left many people homeless

“Transparency, respect and inclusiveness and children understand the implications of their choices,” she reminded the audience, including South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, two Nobel Peace Laureates and high-profile delegates from the labour movement.

While the children’s narratives were moving, government, labour, business, and NGOs dealt with the challenges of fighting the scourge of child labour and finding ways to meet the 2025 deadline to end the practice in a world hit by wars, displacement, and the pandemic.

Vice President of Workers Federation and Cosatu leader Bheki Ntshalintshali questioned how when the “world is three times richer, 74% are denied a social grant.”

“Poverty leaves children vulnerable,” he said.

Ntshalintshali called for a “new social contract” to end child labour, noting that four out of five children were forced to work in the agricultural sector in sub-Saharan Africa.

Jacqueline Mugo, of the Federation of Kenya Employers, acknowledged that it was crucial, though not easy, to reverse the increased child labour trends.

“No doubt it is even more crucial than the previous conferences to succeed and galvanise to end child labour … If we fail to address the root causes, we won’t surely succeed,” she said.

2014 Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi, who has been fighting child labour in India and elsewhere for 40 years, remained upbeat despite the setbacks.

He noted that while the wealth of the world had increased, yet the plight of the children had worsened.

“I am angry because of the discriminatory world order, and the still age-old racial mindset. We cannot eradicate child labour without eliminating it in Africa. We know what the problem is and what is the solution. What we need is, as Madiba said, (for) concerted action is courage,” Satyarthi said, referring to South Africa’s first democratic president Nelson Mandela.

He said it was time to rise above partisan politics, adding that it was possible to reduce child labour once again.

Nosipho Tshabalala facilitated a discussion on child labour where Stefan Löfven, former Prime Minister of Sweden, spoke about the challenges of the labour market and supply chains and how we could use climate transition to create jobs.

Leymah Gbowee, another Nobel laureate, did not pull any punches when it came to Africa’s dismal record of child labour.

She slammed African governments who paid lip service to the goal of eradicating the abuse of children.

“When the cameras are off, suddenly politics come into effect … Africa is responsible; our governments are not blameless,” she said, reminding politicians that “our children are key to any policy, not the politics.”

Minister of Employment and Labour Thulas Nxesi was also critical, saying: “We pass resolutions, grand plans but no implementation.”

But he also defended SA, saying the country provided safety nets for vulnerable children through grants and free meals a day

ILO DG, Guy Ryder, called for a human-centred approach to end child labour.

“Child labour occurs in middle-income countries … always linked to poverty and inequality. More than two-thirds of the work of children happens alongside their families,” Ryder said.

These children were then excluded from education.

Representative of the UN in the African continent Amina Mohammed, and chair of the UN SDGs, said via a hologram: “Child labour is quite simply wrong. The ILO has a critical role in this work.”

She noted that a “lack of education opportunity fuels child labour”.

Saulos Klaus Chilima, Vice President of Malawi, called for urgent action, saying: “We will we get there. We will achieve what we desire to achieve. I believe we can overcome.”

President Cyril Ramaphosa, in his address, commended the ILO for being at the forefront of global efforts to eradicate the practice of child labour.”

“Child labour is an enemy of our children’s development and an enemy of progress. No civilisation, no country and no economy can consider itself to be at the forefront of progress if its success and riches have been built on the backs of children,” he said.

Ramaphosa said South Africa was a signatory to the Convention of Children because “such practices rob children of their childhood”.

He noted that while for many people, child labour “conjures sweatshops … there is a hidden face it is the children in domestic servitude to relatives and families.”

“We call on all social partners to adopt the Durban Call to action to take practical action to end child labour. We must ensure by all countries ILO convention against child labour; universal action to universal social support,” Ramaphosa said.

The 100 Million campaign, supported by KSCF US, led the youth delegation to the Fifth Global Conference. Lucky Agbavor is a member of the delegation.

Originally published by IPS News, 15 May 2022, available here.